|

The K1931 is a straight-pull bolt-action

rifle and was not well known in the United States until recently.

|

These

rifles were not

known very well to American collectors and shooters until rather

recently. When they began to be imported in larger numbers and sold for

remarkably low prices, their reputation for accuracy and affordability

spread quickly via the Internet. Some experts estimated that a rifle of

this quality wouldn’t leave the factory for less than $1,500 today. I

was intrigued and bought my K1931 for less than $100.2

|

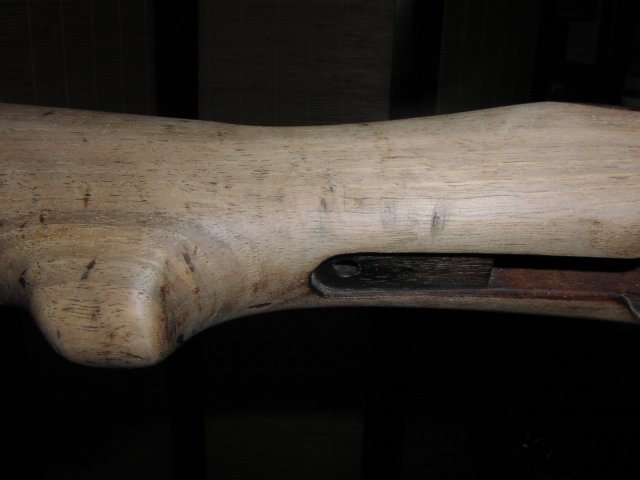

Overall, my K1931 was in very good

condition, but its stock had suffered many dents and gouges.

|

When

the rifle arrived, I

was immediately impressed. My K1931 was assembled at the Swiss Federal

Arsenal in Bern in A.D.

1941 had last been

issued to Bernard Chevalley (b. 1942) of Lausanne. Its walnut stock was

typically battered, with the dents, gouges, and worn finish not

unexpected for a rifle that spent its military career in the snow and

ice of the Alps, but the metal was in nearly perfect condition with

very little wear to its original bluing. The speed of the carbine’s

straight-pull bolt action also rivaled that of the British turn-bolt

Lee-Enfield rifles.

On top of all this, my carbine was complete. It had all its original

parts, which were numbered to match the receiver. On closer inspection,

however, I noticed the cantonal repair markings on the stock and

receiver tang. The edges of the wood had already been rounded by a

previous refinishing episode.

Confident that I wouldn’t be harming a historical relic, I decided to

refinish the stock and try to remove some of the dents. I disassembled

the rifle and proceeded to clean its parts. I washed the stock with Murphy Oil Soap

and removed the remaining finish with odorless mineral

spirits. Thankfully, I didn’t have to deal with the cosmoline common on

other surplus firearms.

|

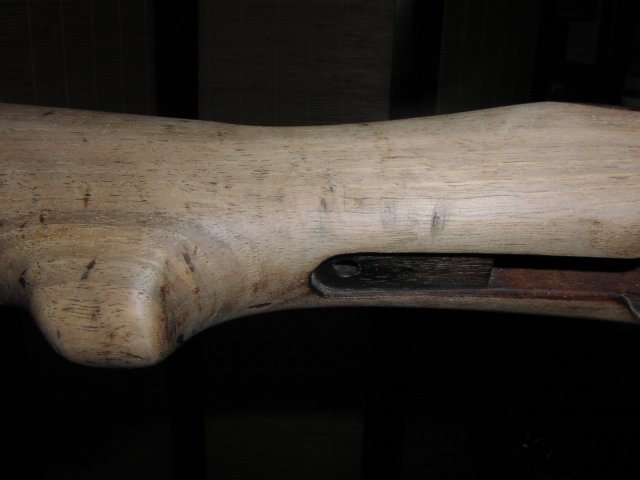

I removed the old finish from the wood and

smoothed out many of the dents.

|

Of

course, once I had my

carbine taken apart, I found some rust hidden under the wood. There

were many small spots of stable, black rust on the barrel. I smoothed

these out with my trusty stainless-steel pot scrubber. Fortunately,

there was no red rust, which can be a sign of rapid corrosion.

I used a hot iron and a damp washcloth to steam many of the dents out

of the stock. This process was quite successful but also raised the

grain of the wood in many spots. Working with fine sandpaper, I

carefully smoothed everything out again. At this point, I noticed a

previous and rather skillful repair to an incipient crack.

|

Three dowels mark an earlier stock repair

at a Swiss arsenal.

|

Rather

than trying to

replicate the shellac used by the Swiss, I decided to apply a more

modern finish to the stock. I selected Birchwood Casey Tru-Oil for

the job. Applied in thin coats with a clean rag, it quickly developed a

glossy sheen but also brought out the natural figuring in the wood

rather nicely. Pleased with myself, I left the parts to cure for a week.

|

Tru-Oil left a shiney, somewhat sticky

finish. Note the scars where I had raised dents in the wood.

|

When

I returned to the

stock, I was not so pleased. The finish remained slightly tacky in

certain spots, and no amount of rubbing with a clean cloth seemed to

help. Reluctantly, I turned to the very fine steel wool. This would be

my first time using steel wool in this capacity, so I was worried that

I might do more harm than good.

Following the grain of the walnut, I gently buffed the stock with the

steel wool and was happy to see that I wasn’t removing the new finish

or scratching the wood itself. After a few minutes, the tackiness was

smoothed out, and the glossiness was reduced to a pleasant satin. I

then wiped the stock clean with a paper towel and removed the remaining

fragments of steel wool with a powerful magnet.

|

After buffing with very fine steel wool,

the finished stock looked and felt much better.

|

As I

noted earlier, the

metal parts of the carbine were in excellent condition. The bluing was

worn only in few spots, most significantly on the butt plate.3 I

refinished the plate with Brownells

Oxpho-Blue but left the rest of the metal alone. After this,

reassembling my carbine was all that was left for me to do.

In the end, my K1931 required very little work. I repaired some

cosmetic damage to the stock and gave it a new protective finish. The

rifle still bears some of the scars of its decades of service and

storage, but it also remains as ready for action as it was over 60

years ago.

|

I gave the stock of my K1931 an attractive

new finish but did little else to the carbine.

|

And

yes, the K1931 rifle

is

even better than a Swiss watch. It can shoot.

|

1

|

The

K1931 was officially a carbine, but by the middle of the 20th century A.D., most military rifles had been reduced to

“carbine” length, whether they were called such or not. Service rifles

and carbines have continued to shrink since then, making the carbines

of the Second World War look more like long rifles today.

|

2

|

At

one point, K1931s were priced so low that their bayonets commanded more

money than the carbines themselves!

|

3

|

This

seems to be a common problem on K1931s. In fact, it’s so common that

some collectors have questioned whether the butt plates were even blued

in the first place. I have seen ample evidence to conclude that they

were.

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright

© A.D. 2007

by M. D. Van

Norman.

|

|